This post is simply to provide a brief explanation of what is currently happening with the Japanese economy. As recent news have explained, there has been tremendous pressure in the Yen, which has caused it to depreciate relative to the US Dollar. For example, on January 1, 2022, you needed to pay about 115 Yen to purchase $1; and as of July 4, 2022, you now need approximately 135 Yen to purchase the same $1. This means that so far this year the Yen has lost about 17.4% in value relative to the Dollar. At a basic level, the loss in value has to do with supply and demand issues: people are selling the Yen and buying US Dollars.

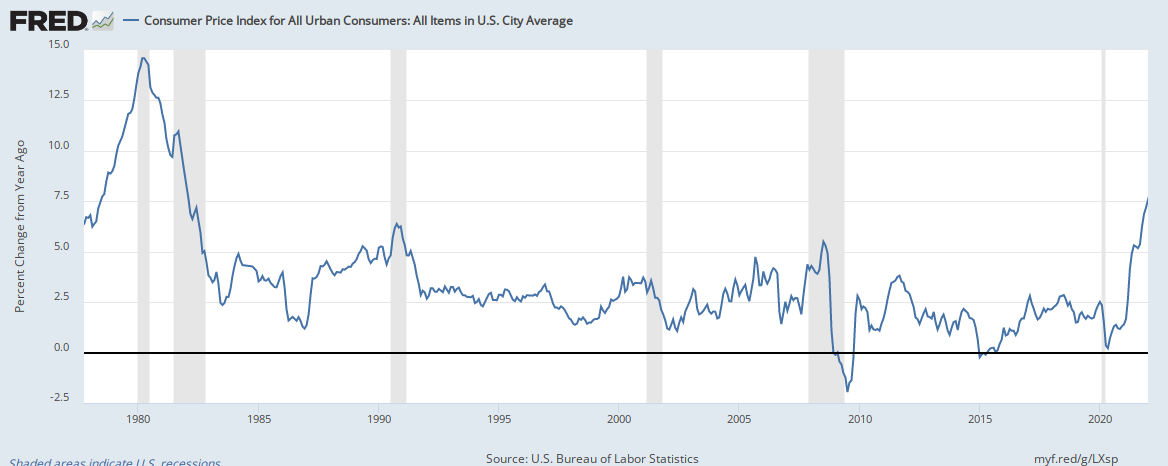

Why are people selling the Yen? Because investors have determined there are better returns in an alternative currency (i.e US Dollars). And right now, in terms of investment returns, the US provides an appealing opportunity. Japanese bonds (10-years) are currently paying somewhere in the neighborhood of 23 basis points – about 2.5% less when compared with similar US bonds. Furthermore, with consumer price inflation running hot and as a result the US Central Bank has begun to increase rates, this means that from an investment perspective US bonds are increasing their appeal. As such, people sell bonds and buy US treasuries – which essentially means selling Yen and buying Dollars.

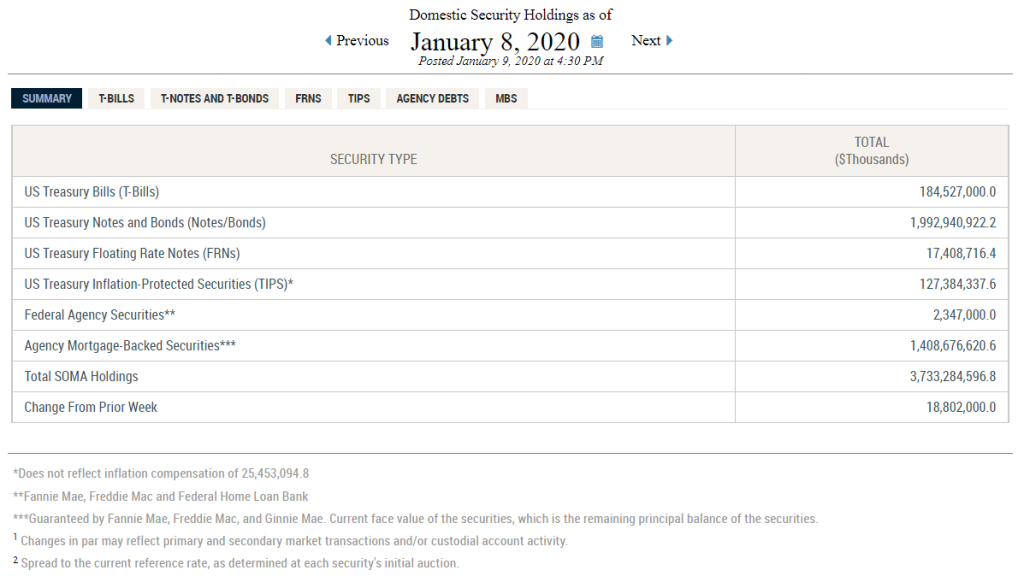

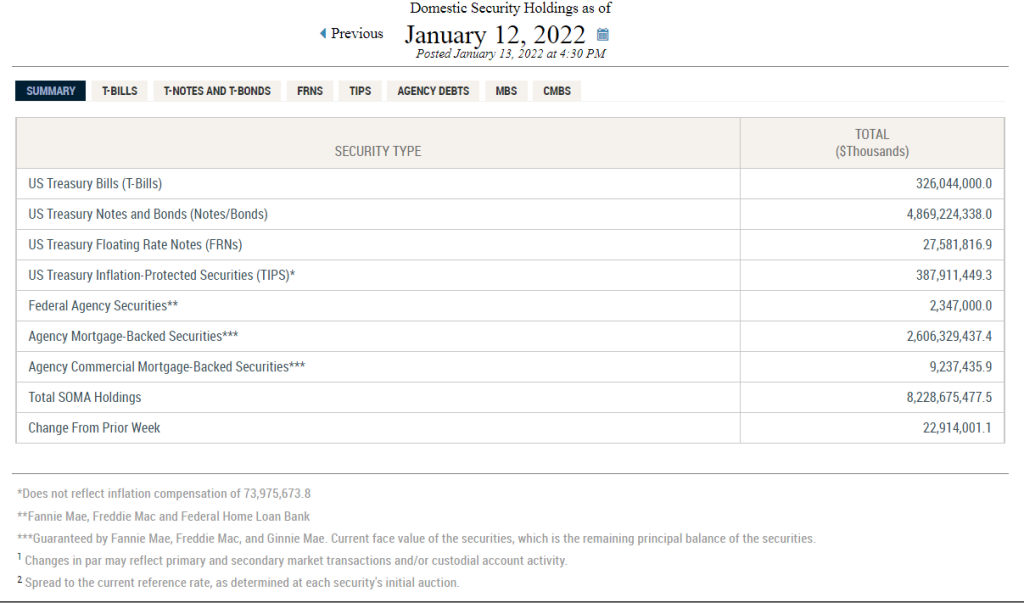

This puts additional downward pressure in Japan for the demand of their bonds. This causes bond prices to fall, thereby increasing yields. On top of this market phenomenon, as part of its monetary policy, the Central Bank of Japan is committed to maintaining a maximum of 25 basis points for its 10-year debt. But as the bond selling pressure increases, the BOJ is doing what they can to assure that interest rates do not exceed the central bank policy target rate of 25 basis points. This means that any excess supply of debt, the BOJ is buying. And when the BOJ buys, it is increasing the money supply, which devalues the currency. It is becoming a pernicious cycle.

How long with the BOJ continue to do this? We don’t know

for sure. What we do know with fair certainty is that what the BOJ is doing is

not sustainable. Judging from prior history (see Asian Crisis of 1997-1998 to

get a sense of what could unfold), we know that this will not end well.